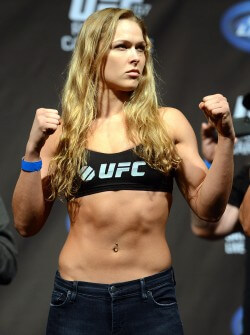

Judo helped turn Ronda Rousey into a superstar!

On Saturday, Ronda Rousey will defend her UFC crown for the first time since being named “the world’s most dominant athlete” by Sports Illustrated

If recent history is any indication, it won’t take long — her past two title fights lasted a total of 30 seconds— for Rousey to demonstrate her superiority in mixed martial arts, not to mention the discipline in which she once specialized: judo.

The biggest star in MMA, Rousey has brought new attention, at least in the United States, to judo, and I decided to acquaint myself with it. Or re-acquaint myself, I should say, because I tried it when I was a first-grader; that was way back in the 1970s, and pretty much all I remembered was a throw called osoto gari.

We didn’t do osoto gari on the evening I stopped by a recreation center in the District to join a class taught by the folks at DC Judo. But we did enough other stuff to give me firsthand evidence that the martial art and Olympic sport could serve pretty darn well as not just a form of competition and/or self-defense, but as a great workout.

Naturally, Marti Malloy agrees. When I talked to her, she had just won a gold medal in judo at the Pan Am Games, and in 2012, she became only the second U.S. woman to reach the podium in the Olympics (Kayla Harrison subsequently won gold for the United States at those Games), following Rousey, with whom Malloy had countless bouts when they were both youngsters.

“Judo is one of the sports that is all-encompassing,” Malloy said. “So it requires you to be strong, it requires you to be fast, requires you to have agility, good dexterity, hand-eye coordination, speed. Obviously, when you first start judo, you don’t need to have all those things, but just from doing what the sport requires, you develop them.”

If my experience was any indication, starting judo is the roughest part, at least in terms of the warm-up exercises involved. The 30 or so of us in attendance went from one side of the padded floor to the other in a variety of difficult ways — somersaults, backward somersaults, handstands, bunny hops, a body-drag and an assortment of tumbles — designed to get participants breaking a sweat while mimicking movements demanded by the sport.

While I, as a newcomer, sat out some of the tumbling exercises (okay, I also skipped some of the other stuff), I learned that becoming good at falling to the mat is a critical initial skill.

“That’s probably the number-one most important thing that you need to learn, especially for kids,” Malloy said, “because when judo is done correctly, in my opinion, it’s perfectly harmless. . . . You need to learn how to absorb that shock of hitting the mat with your body.”

My DC Judo instructor, Terence McPartland, decided that I and the other novices should start “from the ground and sort of work up.” He had students pair off, with one lying on the mat while the other practiced a holding technique.

We built from there, learning how to escape from that hold, then how to get an opponent to the mat using a particular throw (osoto otoshi), then how to counter someone attempting that throw, setting him up to go down. A lot of it was wonderfully counterintuitive; the natural instinct in the face of an attack is to move away from it, but judo teaches moving into the attack, then often pivoting quickly and catching the opponent off-balance.

“We’re demonstrating, hey, everyone’s the attacker and everyone’s the defender at all times,” McPartland told me afterward. “You know, you can sort of switch roles at any moment.”

That skill is what makes judo an effective form of self-defense. “Usually, when someone is attacking you,” Malloy said, “it’s a bigger person who thinks that their size and power and strength is going to be able to take whatever it is they’re trying to take from you. But with judo, what you learn is a manipulation of balance,” using their momentum against them.

Michael Landstreet, head instructor at the Arlington Judo Club, said, “If you throw the person correctly, they should feel like they only weigh 30 pounds.” He mentioned a pair of occasions when he was threatened with a weapon (a gun and a knife) and he chose judo instead of taekwondo, in which he also holds a black belt, to successfully subdue his assailants.

Both Landstreet and Malloy cited the mantra “maximum efficiency with minimum effort,” which is credited to Jigoro Kano, who created judo in late-19th century Japan. Of course, while that is certainly the goal, it still takes plenty of effort to get to that point.

My training partner at the DC Judo class was less interested in getting into shape (he was pretty much already there) than in learning what have become essential skills for MMA. Nicholas Dudek, a 21-year-old student at American University, came to the program several months ago with an extensive background in various disciplines, such as Shotokan-style karate and taekwondo, that emphasize striking opponents.

“There is no other martial art that will teach you throws, and how to prevent against throws,” he said. “So if I want to stay on my feet, that’s a great way of doing it.”

Dudek, who admitted that he watches “way too much MMA,” wasn’t sure whether he would actually end up competing in that sport, partly because “the ground-and-pound scares me.” But the slender young man, who is more used to sparring at a relative distance from his opponents, was eager to soak up judo techniques, if only because, as he put it, “you need to learn how to defend yourself off your back.”

More certain that she would not be trying her hand at MMA, at least not anytime soon, was Malloy, who, as something of a successor to Rousey, gets asked that question a lot. Having won a silver medal at the 2013 World Judo Championships, Malloy is focused on achieving her “dream” and taking gold at the 2016 Olympics.

But Rousey’s success is “something that I appreciate,” Malloy said, “because when I talk to people now and I explain judo, they have seen Ronda do her judo in her fights, and so they know what I’m talking about, and that’s gratifying for me.”